Interviews

Interviews are a wonderful tool to connect the reader to an important person or someone of interest within your business, on a deeper level. A good interview can be engaging and leave a lasting impression on the reader; can inspire and pique an interest that can make the reader want to know more.

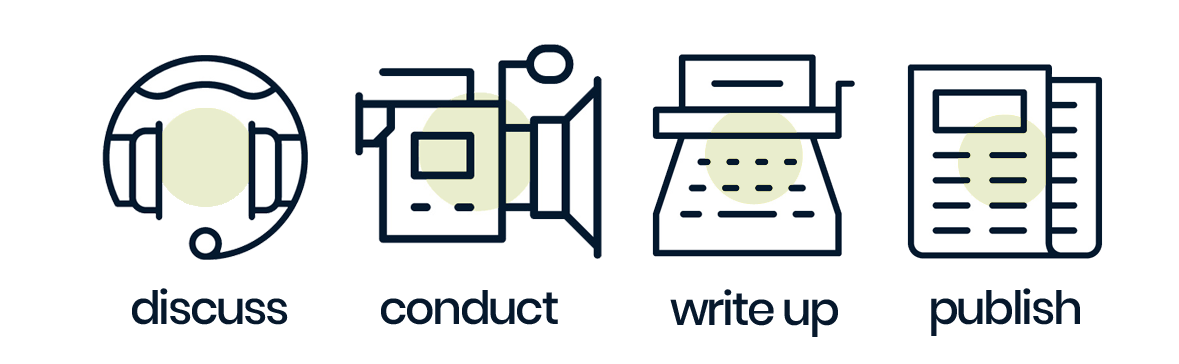

My interview techniques combine storytelling embedded within the answers to the questions to take the reader on an interesting journey. The end result is content that can be chopped up and posted across social media and something that can be used for press releases, newsletters and your websites.

Complete the form below to get started.

Should you have any more questions, feel free to contact me by clicking the button below.

Below is an an example of an interview I conducted for an art magazine.

“Little Girl with Brave Heart”

Leonie Edna Brown’s studio is not far from the idyllic Durbanville Hills and the drive gives me a moment to ponder on something she wrote on her website (www.lifeart.co.za). “Art creates a moment in time for silence and contemplation. It stops me in my tracts (sic) and for that one little moment, nothing else matters but that small breath of peace”. The word ‘peace’, echoes in my thoughts as I traverse the road that dissects Cape Town’s Northern Suburbs. The gorgeous green wine farms that marry the natural contours of the landscape in splendor deserve artistic appreciation, and there is certainly a moment in time here, minutes away from my destination, that evokes a sort of inner peace.

There are more of these insights on her personal blog, about the curative nature of art and the symbiotic relationship it has with healing. Art can help “seek out the light and push away the darkness”, Leonie writes, saying that she wants to “create something that can bring light and change.” As I turn my gaze between the road ahead and the intrepid mountain bikers slicing through the wine farms on the dirt tracks, I wonder about the darkness that exists within this abstract South African painter and where did it all come from?

“I always say that I grew up as a orphan in a family of orphans,” Leonie starts, as we take our seats in her studio, an oblong shaped hall that forms part of the 1st Durbanville Scout Hall. Every inch of it is splattered with paint, some accidental spills from the strokes of a paintbrush, others purely intentional by the artist herself, on canvas and in an array of colour and emotion. Her two beautiful (breed of dogs here) find comfort by her feet and I sip the coffee she’s made me from a metal, paint stained cup.

“My dad, he didn’t really have parents really, he discovered his mother dead on the ground when he was 10 and was sent off to his grandmother, so he grew up without a father. And my mother grew up in a really poor family in Parow. Big families those days were very, very poor. She was seven years old standing on a chair cooking rice on a cold stove, for example.”

It begins as a story of asperity from poverty, for children from two separate families that would eventually become Leonie’s parents. Childlike innocence swept away by a harsh Dickens-esque narrative. “When they got married and I came along four years later, my dad was already an alcoholic. And my mum grew up with a lot of fear as she came from an abusive background, so she was overtly aggressive towards me as well. So I grew up with no protection, actually no parenting. I was looked after, fed, probably loved but they didn’t know how to express it.” I follow her lead in sipping coffee, feeling the neglect in my heart as she speaks.

“If the parents are not there to protect the children, then the children are open to all kinds of abuse. So from a very young age, I was sexually abused by family members. My dad was working for a Government Institution at the time, so from people within the Institution as well.” I feel my heart sink but I feel strangely at ease with everything because I already a got the impression, when we shook hands and greeted that I was in the presence of a very strong woman.

“Alcoholism has a massive impact on children in any case and abuse teaches you not to trust authority,” Leonie continues telling me. “You cannot trust anybody and it affects your whole life. I had my first boyfriend when I was fifteen and I was date raped. This guy was obsessed with me and I couldn’t get rid of him. I was basically, for two years, raped three times a week and I had no control over it. I didn’t trust my parents so I couldn’t go to them.”

In the corner of my eye, there’s a painting that I later learned is entitled “Out of the Storm, Into the Light.” Strokes of rust brown, crimson red and mould green combine in terrifying swirls. So much of Leonie’s pain immortalized by the hardening of clay and acrylic paints on canvas.

“Throughout my early life, I ended up with abusive men. Either psychologically abusive, or physically abusive. I was with a guy from when I was about 15 to 18 and he used to beat me, he tried to throttle me a few times, even tried to kill me. I eventually fell pregnant. Not by choice. My mum didn’t take it very well. My mum rejected me. The baby was born at 7 months, dead. I believe the child died because, I, at that point (being a child myself), hated the child. I cursed that child.”

The coffee in my cup has gone cold, but the heat emanating from my hands is enough to trick my mind into thinking that it’s still hot enough to drink. It’s the sheer intensity of the story that causes my palms to feel hot and sweaty. Leonie continues at a pace that leaves me no time to come to terms with her thinking that she was to blame for the death of her stillborn.

“I managed to make matric, I managed to get away from this guy, finally. But even through Varsity (University), it was the same pattern,” Leonie puts her cup down. “Psychologically, your brain is amazing. You just shut down. I just decided that this didn’t happen to me. But your soul, your spirit. It’s all there. It’s like a big storm inside of you. So I did really well at Art in Varsity, but nobody knew what to do with me, because I was unteachable. I didn’t trust anybody. I mean how? Especially me. How do you trust a man?” I nod in agreement, hoping that it comes across in an empathetic way, rather than sympathetic - not in my entire lifetime could I ever feel what she felt.

Leonie made it through the 4 years and received a degree and a diploma in art and teaching. She attributes her success at Varisty to the “risk” she took in studying teaching with art as a second subject to get a bursary, as in her second year she changed her course to only focus on art, something that is strictly forbidden now. She was good at art, she tells me, even has a painting from when she was 15 years old that was so good, her mother called up the school to tell them to stop doing her work for her. But she never saw herself as an artist, or someone who could have a career in art because her mother’s voice hit the notes of self doubt.

After Varisty, Leonie tells me how nothing brought her any peace, and despite making New Year’s resolutions to change, to rid the pain from her upbringing, she ended up “building a bigger and bigger wall” and hiding behind those towering, defensive walls was a very lonely girl. But the sheer amicable resilience of her character meant she didn’t give up trying to find hope.

“When I found religion, when I decided to give my life to God, it was the beginning of a change. When I did that, I stopped painting for 10 years. When I look back, I did that because I needed to change. Inside.” She points to her heart. “I left everything, left Pretoria, left my family and everyone and I came to Cape Town. I didn’t have a job and I was alone with my dog. I took the first job I could find, in graphics and started again.” This is the point in the interview where I learn the meaning of the name Leonie: Little girl with a brave heart. She fought off the currents and swam upstream and found herself able to rebuild.

Through the vicissitudes of the ten years, Leonie felt the continual pull back to art. She worked in the corporate world doing graphic design, but despite it teaching her business skills, she said it “was limiting” and she missed the unpredictability of painting an abstract piece. “After the second year of work, it started to become reptitive. It’s Valentine’s Day, it’s this day and this day, you just have to come up with a new design and you already know how to do it but with paintings, you never know what you are going to get! But working was a good learning experience as it taught me valuable business skills.”

But possibly the most momentous lesson learnt, as she was trying to find herself “through a thick forest” of pain was that of trust, which partly came in the form of a female boss. “She didn’t believe in what people said about me but looked at me as a person and as an individual. She taught me that there are people in authority that I can trust.” The building blocks were there with religion and a positive authority figure in the form of her female boss and so Leonie was learning to trust all over again. But she till lacked that person to walk beside her.

“In 2000, I started painting again. In 2001, I met my husband. He was the one that also helped heal me, he’s a wonderful man. When you get married, your fears and frustrations you take out on the closest person. You hurt the person you love the most because somebody has to pay. In my case, he had to pay because of what happened to me. I was so angry because of this history of abuse.” She talks with a genuine, vibrant love gleaming in her eyes as she tells me of the man, her husband, who held her close through the tears and the fights and steadied her soul to heal. “Reflecting pain is very emotional.” She lets out a laugh and I follow suit, her story echoing inside of me like the voice of little girl lost down a well.

We begin to talk a bit more about Leonie’s art and her relationship with her paintings, and the whirlwind of emotions that still exist in every stroke of the paintbrush, so many years after what was inflicted upon her.

“It’s not like a bin that a truck takes away. That rubbish stays there. It’s part of you. You have to take it out, look at it and clean it up. That is, for me, going back to why I paint what I paint. Sitting in that place of darkness doesn’t bring healing. Regurgitating that pain and vomiting it out on the canvas helps. And it might be able to help somebody, somehow, subliminally, to realise there’s is something more for them than this place they are in right now. I don’t want to help people sit in the prison, I want to help people get out of the prison of their emotions. I want to create something where somebody can look at it, and if they have gone through the same experience, it brings hope. Hope that they too can heal.”

It’s a powerful emotion, hope. It’s in every corner of Leonie’s paintings, in every layer and in every stroke. Because she projects the way she was able to heal in her work and, looking at it, I am awash with that emotion. “We have to face the things that we have gone through. I have to face the fact that people hurt me, but I need to forgive them because if I don’t forgive them, it’s like me drinking the poison and hoping that they will die.”

I want to learn more about abstract art and specifically, Leonie’s methods, so I move on to asking her about her processes. “I experiment a lot. I combine things that I shouldn’t to see if it works. What I do is very experimental. That’s how I discovered encaustic painting, through experimenting with hot wax and resin.” There’s definitely a freedom about her paintings, a flow that reminds of waves breaking at the shoreline. I ask her if all of her works are experimental.

“There are certain rules, elements of design that you need to take into account that makes a better painting that I learnt at Varsity, but you have to be willing to break the rules and to know why you want to break the rules.” Leonie stands up and leads me to a series of unfinished paintings resting on a long, paint stained table. “At the moment, I am trying to combine abstract with human figures - again, some experimental stuff.”

The large painting that now stands behind us is not to be ignored, despite being unfinished. It cradles you in giant, resplendent hands and swallows you up in one, swift, biblical gulp. Leonie catches me marveling at and I comment on the religious connotations that weave themselves between the figures she’s painted.

“If you can’t hold on to yourself, you have to hold on to something. We all know that there is something bigger than us. Look at the intricacy of how we are made, our fingertips for example. We cannot recreate out of nothing. Look at every person who is uniquely individual.” Leonie wonders back to her seat and I follow, along with her two dogs. “When we look at a sunrise or a sunset, there is something in us that sings. There is, must be, something bigger…”

I agree to that, not blindly giving in to her opinion but rather embracing what she says in wonderment. Here is someone, who despite everything that has happened to her, still holds faith dear to heart. But religion isn’t the only influence in her work, so I ask if there are any other influences.

“I love the works of Van Gogh. He had a desire for more. He never got to it though, he was very suicidal but there is such a desire for life in his work. Michelangelo had some unfinished figures in Florence, I remember seeing them and they made me cry, these figures trapped in rock that he was still chiseling away before he died.” We talk for a moment about inspiration and how, in the art world, it can be misconstrued as plagiarism when really, it is about being shaped by your own individual interpretation of other artists’ work.

But all that Leonie spoke about prior to our engagement over art and inspiration, still clings to my consciousness. So I bravely ask her thoughts on the recent ‘metoo’ movement. After all, who better to wade through a topic such as this then with someone who almost drowned in it.

“The person that is abused becomes shameful because they think that it is there fault. For many years, and this is something that I still have to work through, I thought that there must be something inherently wrong with me. That there is something in me that attracts this Sometimes people don’t speak out because they are ashamed of being rejected because they are already rejecting themselves. Self-hatred. So, how do I expose myself if people are going to hate me more?”

It’s a reoccurring pattern of women tussling with the idea to come forward and Leonie helps me understand why. It’s the crippling fear that keeps their secret locked away. To admit to abuse is to expose yourself to the world, a world that just might not believe you. I wonder then, how Leonie even has the strength to surround herself with men after everything.

“Not all men are evil. Men can be wonderful. If you look at a little girl, her girlishness gets established by her dad, at a young age, five to seven, treating her like a little Princess. That’s what makes her into a girl, that’s what makes her precious. Currently, there is an attack on men and the manliness of men, and I don’t think women should look at men as all evil. We all have a darkness in us from time to time. Men who abuse women were often abused themselves, so you hurt others because you were already hurt so badly.

“I think the world needs strong men. Strong men establish families. When I look at my husband, he is a strong and gentle man, he is a wonderful man. He is kind and because he is strong, he makes me feel secure. I trust him. If I can trust him, I can be who I want to be. He helps me be who I want to be. I think that if there are strong men, strong fathers, there won’t be boys and girls who grow up with so much hatred towards others, wanting to hurt and abuse to prove something. So we need fathers. Strong male examples that stands for the right thing.”

But then, would this feed in to everything that Feminists stand against?

“Before I got married, I was a very independent, a very strong woman. Nobody told me what to do, I told them what to do, I was very self sufficient, didn’t need nobody. But I wasn’t happy. If I look at myself now, I am still independent, still self sufficient but, I am secure. Because I have a strong man who loves and supports me.”

Leonie talks about balance. Being independent, strong minded and self-sufficient and secure from a love from a partner. It’s a message of unity, in her case, from the strength of her husband, who held her tight through the tears. It’s a story of finding forgiveness. I ask her then, since the abuse she experienced happened in South Africa, if she would ever leave.

“I love my country. I believe in this country. My husband is English and has a British passport and We can easily go to England, Scotland but both of us love Cape Town. We feel that here is where we are supposed to be right now.” Even though, she tells me, she sells most of her art in America she has seen the power of social media and how “you don’t have to be anywhere specific anymore.” If America, then the state of South African market must be difficult?

“Tough. Very, very tough. The world economy is very wobbly and in South Africa it is not different. Here you have to have the gift of the gab and do something weird and whacky with your art. A good story sells. Conceptual art. It is all about telling the story and selling the story. The rest of the world is going back to skill. To being technically proficient. But South Africa art is full of colour.” But despite this, there is no desire to leave and start again in a market that could be more receptive to her work.

“I give classes 3 times a week and I have done since 2004 and I look at the work from my students, it’s totally out of the box. It’s always something new because we are so diverse. We have this wonderful diverse culture of so many nations thrown in together and we all influence each other. So that diversity brings something to this country and to the art that isn’t accessible anywhere else. I’m here, I love what I do, I love teaching. I love seeing what the students are doing and I love helping them, and I love seeing the bright future that each one has in them.”

On the drive home, after a conversation that eclipsed an hour, I find myself playing this part of the interview over and over again:

“I wouldn’t wish it on anybody else, but I am not sorry that it happened to me because it has made me who I am. I am not shy about what happened to me, I am happy to share it because I have survived. I am now living a full and happy life, happily married to a wonderful man. I am sharing it to say that it is possible for somebody who is in that pit of despair and I know what that pit feels like, so I can say, ‘I was actually once where you are now, come, let me grab your hand’, even if it is through my paintings. That painting will go where it is meant to go and it will talk to who it is meant to talk to.”

Leonie. Little girl with a brave heart.